When one of the ducks living in the Lake at

Constitution Gardens needs help, Ted Woynicz is the man to call.

|

Ted's ducks live within a waddle

of the Washington Monument and the Reflecting Pool |

long a busy stretch of

Constitution Avenue,

across from the Federal Reserve building,

Ted Woynicz leads a visitor to his special place. long a busy stretch of

Constitution Avenue,

across from the Federal Reserve building,

Ted Woynicz leads a visitor to his special place.

It's informally dubbed "The Lake at Constitution Gardens,"

a 7.5-acre, island-dotted jewel flanked by the Washington Monument and the Reflecting Pool.

But Ted has another, even more casual, moniker for the lake.

"Welcome to the land of the ducks," he says.

Known to his cohorts as "Ted the Duckman," the Florida native

is one of more than 200 greater Washingtonians who serve as National Park Service

VIPs - Volunteers in the Park. They are typically volunteers who lend a particular

professional or personal expertise or skills to their duties.

And for most of his life, Ted has been interested in ducks.

Raised on a 1,000-acre farm at the edge of the Florida Everglades, Ted grew up around

3,000 head of cattle, 200 horses, dozens of dogs and cats-and hundreds of ducks.

He started as a zoology major at the University of Florida in the late 1970s, before

graduating with a degree in visual design. He later earned a professional certificate

in neurolinguistic programming from the society of NLP while attending George Washington

University.

Ted has served as VIP at the lake for nearly six years. And although

he's officially a volunteer, he comes to the park most every day. In a year, he'll log

700 hours at the lake, or nearly five times beyond volunteer minimum.

So park officials consider Ted the steward of the lake. He's the one to alert them when ducks

lay eggs, and when they hatch. He gives the heads-up when the algae is getting bad.

"He's our eyes and ears out there for so many things," says Gregg Kneipp, a natural resource

management specialist at Parks Central. "So he lets us know when he sees something that

needs attention, and he often sees it well ahead of us."

Today, wearing his park uniform, Ted slowly circles the edge of the lake. Walking along the

4,200 feet of shoreline, he finds bits of discarded Americana - potato chip bags, soda cans,

hundreds of feet of fishing line, house keys, watches, cameras, running shoes, even a rusted

tricycle.

He picks up every piece and disposes of it properly.

These items have no place in their home, he says ("them" being the ducks, of course).

Hundreds of human visitors come uninvited and leave such trash, but Ted is

too civil to be impolite.

|

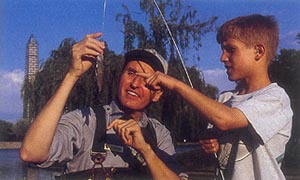

Volunteer Ted "the Duckman" Woynicz spends more than 700 hours a

year watching over the waterfowl living at the lake at Constitution Gardens in

Washington, D.C. |

|

It's not that people dislike the ducks, he explains. Most

love to see them here, a reminder of childlike playfulness in the middle of urban

Washington D.C. These city dwellers leave trash behind because they don't know

any better. Which is why Ted the Duckman keeps coming.

A few minutes later, Ted spots a pair of men whose border collies are running without

leashes. Not that he has anything against dogs either, but they have their place, and

a park filled with ducks isn't the place for unrestrained dogs.

"Gentlemen," Ted says, pointing out his park name tag.

"You'll have to put those dogs on a leash. It's the law. Thank you kindly."

In addition to knowing the law, Ted also calls most of the

ducks by name, and there have been more than 50 named during his years of volunteering.

When I bring my friends here at night,

I can tell from the sound of the quack who the duck is. It's like when you spot

your wife coming out of a crowd at RFK Stadium. It's instant recognition.

Ted Woynicz

"There's Dover, his feathers look like the white cliffs of

Dover," he says. A duck named Mousse has a cappuccino-chocolate look. "There's

Wrinklebeak, a unique snowy mallard, who has a wrinkled beak, and Sabrina, a mallard

hen, who has a smoky gypsy look."

Another lake visitor watches Ted interact with his flock.

"You have names for all the ducks?" He asks.

Yes, of course, Ted tells the visitor.

He does.

"That's alllll-right!" the visitor replies, smiling.

"For me it's easy to recognize the individual ducks," Ted says. It comes from

being around them for thousands of hours," he explains. "When I bring my friends here at night, I can tell from the sound of the quack who

the duck is. It's like when you spot your wife coming out of a crowd at RFK

Stadium. It's instant recognition." The brain can detect consistent patterns. I can

detect the same [such as shapes, quacks, plumage] from these ducks."

Ted points out

O , a very special duck indeed.

He found an egg unhatched amid a nest where 12 ducklings had just been born. He knew

that late ducklings, "those taking more than 24 hours to hatch after the first duckling

hatches," are often left behind. , a very special duck indeed.

He found an egg unhatched amid a nest where 12 ducklings had just been born. He knew

that late ducklings, "those taking more than 24 hours to hatch after the first duckling

hatches," are often left behind. |

|

He's our eyes and ears out there

for so many things. So he lets us know when he sees something that needs

attention, and he often sees it well ahead of us.

Gregg Kneipp, Natural Resource Management Specialist,

Washington D.C. Parks - Central

n executive support

consultant in his other life, Ted had just

finished a meeting with a client one day before heading out to the lake. Still

wearing his suit and tie, he was walking along the water's edge when he discovered

the egg with a little beak sticking out of a small hole and heard two weak cheeping

sounds. n executive support

consultant in his other life, Ted had just

finished a meeting with a client one day before heading out to the lake. Still

wearing his suit and tie, he was walking along the water's edge when he discovered

the egg with a little beak sticking out of a small hole and heard two weak cheeping

sounds.

The egg was very cold, so Ted did the only thing the Duckman

could do. He took the egg home, wrapped it up with towels, lay it on his chest,

put a heatlamp overhead, and hatched it himself. It took 16 hours.

"When she hatched, I was so glad to see that her breathing

normalized that I named her O ,"

Ted explains, "Like oxygen." ,"

Ted explains, "Like oxygen."

Lucky O is now 4 years old. She has hatched 63 ducklings of her own. But she and her brood still

endure the occasional thoughtlessness of visitors. Once Ted had to rush her brother,

Dolphin to a wildlife rehab center because he had swallowed two fish hooks and had

another stuck through his ankle. It took a month for him to heal enough to return to

the lake.

is now 4 years old. She has hatched 63 ducklings of her own. But she and her brood still

endure the occasional thoughtlessness of visitors. Once Ted had to rush her brother,

Dolphin to a wildlife rehab center because he had swallowed two fish hooks and had

another stuck through his ankle. It took a month for him to heal enough to return to

the lake.

Getting Dolphin back to the lake was important. Ted never

separates a family. And they are families, he stresses.

"Most people think animals don't remember. But in reality

they don't forget their bonds," he says. "I brought Dolphin back after a month.

When I took him out of the carrier and put him in the water, you should have

seen his brothers and sisters flapping around in the water. They were so happy to

see each other again, to be together again as a family.

Ted points to two ducks quacking in the distance.

"There's Toby Duck and Amadeus," he says. "Come here, guys. Come here."

And they do, flocking to Ted like children rushing to

greet their father.

|

When he's not caring for the Garden's fowl

residents, Ted helps its human visitors |

Article: Dennis McCafferty

Photographs: Allen Rokach

Southern Living Magazine, March 2000

|

DOING LIKE THE DUCKMAN |

|

For more information on the

Volunteer in the Park Program, contact National Capital Parks - Central,

900 Ohio Drive SW, Washington, D.C. 20024 (202) 426-6841 |

|

|